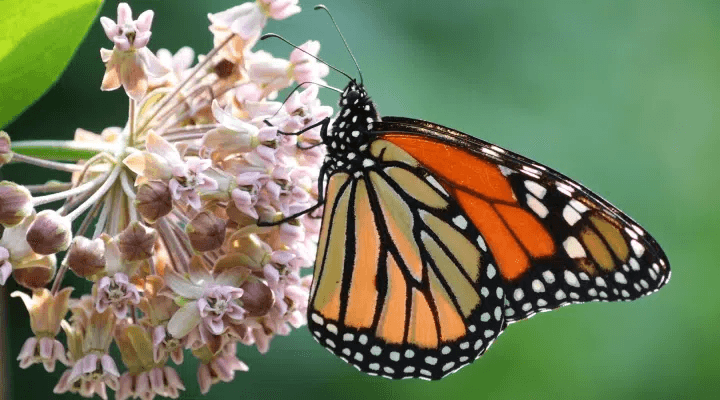

CHICAGO — Monarch butterflies, with their striking orange and black wings, are some of the most recognizable butterflies in North America. But they’re in trouble. Monarch caterpillars can only eat the leaves of milkweed, a native wildflower. As milkweed has disappeared, so have the monarchs, to the point that they’re at risk of extinction. Research shows that planting milkweed in home gardens can add significant monarch habitat to the landscape. In a new study in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, researchers and community scientists monitored urban milkweed plants for butterfly eggs to learn what makes these city gardens more hospitable to monarchs. They found that even tiny city gardens attracted monarchs and became a home to caterpillars.

“In this study, we found that monarchs can find the milkweed, wherever the milkweed is, even if it’s in planters on balconies and rooftops,” says Karen Klinger, a Geographic Information Systems analyst in the Keller Science Action Center at the Field Museum and the study’s lead author. “Milkweed gardens can be in all shapes and sizes, and any milkweed garden can contribute habitat for monarchs.”

Monarch butterflies have one of the most unusual and demanding migration patterns of any insect. The eastern population of monarchs starts the year in Mexico, and they move up across North America in the spring and summer. “As they travel, they lay their eggs, and when those adults die, the next generation continues the migration northward. They will make it all the way to southern Canada, and at the end of summer, a new super generation is born that migrates all the way south and survives through the winter,” says Klinger.

Since it takes multiple generations of milkweed-eating caterpillars to get the monarch population from Mexico to Canada each year, the monarchs rely on milkweed plants throughout their migration path. “There used to be wild milkweed growing along farmland in the Midwest, but now farmers use pesticides that kill the milkweed. As a result, a lot of the habitat for monarchs in the Midwest has disappeared,” says Klinger.

Monarch populations have declined along with the disappearance of milkweed; in recent years, they’ve been a candidate for endangered species status by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and the US Fish and Wildlife Service. “ If we don’t do anything soon, monarchs are going to be in serious trouble,” says Aster Hasle, a lead conservation ecologist at the Field Museum’s Keller Science Action Center and a co-author of the paper.

Since so much of the rural milkweed that monarchs used to rely on has disappeared, scientists have wondered if milkweed gardens in urban areas might be able to bridge the gap. “There was a call for all hands on deck, to plant milkweed across all sectors of the landscape, but people discounted urban areas, because if you look at some mapping of urban areas, it looks like it’s completely developed, with no availability for milkweed plants,” says Klinger.

Klinger was a co-author of a 2019 study led by Field Museum scientists that showed that even “concrete jungles” have room for milkweed plants, in people’s yards, alleyways, and rooftops.

The new study led by Klinger is a follow-up to this earlier work. “With our 2019 study, we found that a lot of the spaces where milkweed could grow was inaccessible to scientists– we couldn’t go into people’s backyards, and look at their milkweed, so there was a lot of milkweed that we can’t account for,” says Klinger. “But we also found that there was a lot of enthusiasm among residents to plant milkweed and support monarchs. So based on that, we did a community science project that became the basis of this new paper.”

Klinger and Hasle worked with volunteers around Chicagoland to monitor milkweed plants in their yards and neighborhoods for monarch butterflies laying their eggs on the plants and caterpillars eating the milkweed leaves.

“We wanted to answer the question of, how well do these urban milkweed gardens actually support monarch butterflies? Everybody always wants to know, what should I plant? What species of milkweed, how many plants, how big of a garden? There are so many questions to answer, so we were hoping that we could use this project and the data from it to start answering those questions.”

Klinger and Hasle trained over 400 community scientist volunteers on how to monitor their milkweed for monarch eggs and caterpillars, which they reported back to the researchers. Over the course of four years, the team collected 5,905 observations of monarch activity on 810 patches of milkweed in Chicagoland. This paper analyzed a portion of this data from 2020-2022.

“We encouraged participants who had planters on balconies, who had planters on rooftop decks, and we saw some of the most amazing things,” says Klinger. “There was one participant who had a planter set on the condominium roof that had five large caterpillars in one photo.”

Based on these observations, the researchers found several overarching trends about what makes for a successful milkweed garden. “There are several native species of milkweed, and we found that common milkweed was very prevalent in people’s gardens and was really key, both in terms of whether monarchs laid their eggs there, and how many they laid,” says Klinger. “Also, kind of surprisingly, that older, more established milkweed plants did a lot better, they were more likely to see eggs than younger plants.” In addition, having a variety of blooming plants was also key for monarchs to lay more eggs on milkweed, as it provided lots of nectar for the adults.

However, while a garden with lots of native milkweed and other flowering plants left to grow year after year might be the best way to help monarchs, the researchers noted that every little bit helps. “Plant the species that works the best for you and your garden,” says Klinger. As of July 24, 2024, Illinois Governor JB Pritzker signed into law the Mobilizing Our Neighborhoods to Adopt Resilient Conservation Habitats (MONARCH) Act, which restricts HOAs from prohibiting native plantings and provides financial and technical assistance for establishing native and pollinator-friendly gardens.

While monarchs are just one small species of insect, they’re indicative of the big-picture health of the ecosystems they live in. “Because they cross this big landscape from Mexico to Canada, monarchs are an important indicator of what’s happening across a big area,” says Hasle. “Monarchs need a lot of the things that other insects need, like blooming flowers, so what’s good for monarchs is good for other pollinators too. And we’re in the midst of a global insect decline, so it’s important to help.”